Ngāti Tama trace their roots to the Tokomaru waka from Hawaiki, and take their name from Tamaariki, one of the five co-captains aboard the vessel. Whakapapa of these rangtira and others aboard, the sagas of their journey and eventual establishment in northern Taranaki are preserved in tribal traditions. Intermarriages between the senior lines of Ngāti Tama and other Taranaki and coastal Tainui tribes forged close relations between these groups.

Around 1820 an alliance of Tainui and Taranaki tribes, including some Ngāti Tama under their paramount chief Te Pūoho ki te Rangi, participated in a raid to Te Upoko o Te Ika (southern North Island). By the mid-1820s these tribes had established themselves at Kāpiti Island and on the mainland east and south to Cook Strait. Relationships based on trade, service provision, and marriage, were established with whalers.

Eventually, the Tainui and Taranaki alliance crossed Cook Strait to Te Tauihu o te Waka a Maui. Te Pūoho ki Te Rangi, other Ngāti Tama chiefs, and rangatira from other iwi led the conquest of western Te Tauihu. After the conquest members of the Tainui and Taranaki alliance, including Ngāti Tama, established permanent communities in the northern South Island.

Ngāti Tama established pa and kainga at several localities in Te Tauihu and at some places in northern Te Tai Poutini (Westland). In Te Tauihu, Ngāti Tama’s main pā were at Wakapuaka (near Nelson) and at Wainui, Takaka, Tukurua and Parapara in Mohua (Golden Bay). Ngāti Tama used the rich resources available in the districts, including flora, fauna, minerals and kaimoana. Te Puoho revisited Te Upoko o Te Ika (and Taranaki) to maintain rangatiratanga within northern Ngāti Tama communities, and to attend to his land interests.

In 1836 Te Pūoho was killed at Tuturau in Southland, along with other Ngāti Tama. Some who accompanied him on the southern expedition were taken captive, including Paremata Te Wahapiro, Te Pūoho’s nephew/stepson. Subsequently, Wī Katene Te Pūoho, although the youngest of Te Pūoho’s four sons, became paramount chief of Ngāti Tama ki Te Tauihu. In 1839 or 1840 Paremata was freed to rejoin his whānau at Wakapuaka.

In October 1841 Company officials, led by Arthur Wakefield, explored western Te Tauihu for a suitable location for a new settlement. Ngāti Tama’s paramount chief, Wī Kātene Te Pūoho, was present at negotiations with Arthur Wakefield at Kaiteriteri and elsewhere. Wī Kātene, his brother Paremata Te Wahapiro, other Ngāti Tama chiefs, and chiefs of other Tainui/Taranaki iwi, received gifts distributed by Arthur Wakefield, in lieu of formal payments for land, which were now prohibited by the Treaty of Waitangi.

During his meetings with Māori, Arthur Wakefield claimed their lands had been purchased in the 1839 deeds, and that the gifts were ‘a present upon settling the land’. Some Ngāti Tama chiefs from Wakapuaka voiced objections to their land being sold by non-residents but accepted the gifts. Chiefs may have seen the gifts as no different to the seasonal ‘rentals’ negotiated with whalers for anchorages and land for wood, water and temporary shore facilities.

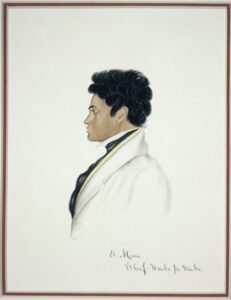

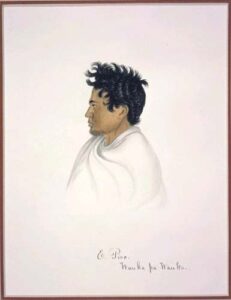

The Ngāti Tama chiefs, especially Wī Kātene Te Pūoho (pictured right), seemed to enjoy good relations with Arthur Wakefield who recorded ‘Emanu [Wī Kātene] is a very respectable man’ (pictured right). ‘Te Kiore’ (Paremata Te Wahapiro, pictured below) and ‘E Haro’ arranged with Arthur Wakefield to allow Ngāti Tama temporary use of surveyed sections in the Nelson Town area for cultivating potatoes and other crops for sale to settlers. Ngāti Tama were to vacate the sections when settler owners arrived in Nelson.

The Company planned 1,100 allotments in its Nelson settlement scheme, each to comprise one 1-acre Nelson Town Section, one 50-acre Suburban Section, and one 150-acre Rural Section, requiring 221,000 acres. Each section was to be chosen by investors in the scheme according to orders of choice assigned by ballot in London. Māori were to have one-tenth of the settlement lands across Town, Suburban and Rural sections.

By April 1842 the town of Nelson had been surveyed. Surveying then began at Motueka and Moutere. The Company surveyor, Samuel Stephens, assured Motueka Māori they would retain their extensive cultivations. The Company, however, included all Māori habitations, cultivations and wāhi tapu in the land it surveyed for selection by the settlers or as Tenths Reserves to be leased to settlers. The resulting displacement of Māori families caused several violent exchanges with settlers.

Wī Kātene Te Pūoho

Te Kīore Paremata Te Wahapiro

Ngāti Tama was directly involved in disputes and confrontations with Company officers and settlers over the northern boundary of the Nelson settlement with the Wakapuaka block, a main area of Ngāti Tama occupation. A settler’s house was pulled down at Wakapuaka in July 1843. In 1845 Paremata Te Wahapiro assembled armed volunteers but the situation was defused without violence. In 1847 Wī Kātene Te Pūoho (pictured above) disputed the survey of the western section of the same boundary of the Wakapuaka block; Pitama Iwikau, a Christian resident at Wakapuaka, was instrumental in resolving that confrontation.

William Spain was the Land Claims Commissioner appointed to investigate the New Zealand Company’s land claims in New Zealand. Commissioner Spain first inquired into the Company’s Te Tauihu claims in June 1842 while conducting hearings in Wellington. Spain’s hearings in Te Tauihu started in Nelson in 1844. George Clarke Jr attended Spain’s Nelson hearing as Sub-Protector of Aborigines to represent and protect the interests of tangata whenua. Spain was assisted by his interpreter Edward Meurant who visited several pā and kainga before Spain’s arrival in Nelson.

Spain first heard from Company witnesses. These were followed by a rangatira from another iwi who testified that only certain places had been transferred for European settlement. Colonel Wakefield and Clarke told Spain that this rangatira was not telling the truth and asked for the hearing to be adjourned. Before the hearings reconvened the next morning, Colonel Wakefield asked Spain to suspend the inquiry and adopt an arbitration process, which had already been used in other areas, to negotiate a further payment by the Company to local Maori in order to complete the purchase.

Spain agreed and abandoned the hearing of further witnesses. Other chiefs, including Paremata Te Wahapiro (pictured above) of Ngāti Tama, who may have intended to testify, were thus prevented from doing so.

On 24 August 1844, following arbitrated negotiations, it was determined a further payment of £800 would be paid to Maori of the Nelson districts. Three Deeds of Release were signed by representatives of Ngāti Tama and other iwi as receipts for this payment and the relinquishment of present and future claims.

Golden Bay chiefs, including Ngāti Tama, had not been present at the Commissioner’s hearing and at a hui at Motupipi refused to sign or accept the £290 allotted them. They stated that they had been previously unaware of the value of the coal on their land and now sought a large payment for it. The money was lodged in a bank until the chiefs, decided to accept which they eventually did in October 1845, signing a deed of sale, rather than a Deed of Release. Te Meihana Te Ao, senior Ngāti Tama chief at Takaka, later complained that he did not receive a share of the payment intended for him.

In 1847 a Crown representative and a Company official visited pa and kainga along the Abel Tasman coast and throughout Golden Bay to set out reserves for local Māori ‘sufficient for their present and future wants’. The Crown official was authorised to allocate about 2,000 acres as reserves, but he interpreted his instructions in a niggardly way. Approximately 1,500 acres of Occupation Reserves were established in Golden Bay.

In his final report on the Nelson Inquiry, Spain recommended an award to the Company of 151,000 acres in the Nelson, Waimea, Moutere, Motueka and Golden Bay districts. This recommendation was confirmed by Governor FitzRoy’s Crown grant of 29 July 1845.

Commissioner Spain attempted to rectify the problem at Motueka whereby pa and cultivations had been included in the sections surveyed by the Company as Tenths Reserves or for allocation to settlers. Spain recommended the re-designation of 16 fifty-acre Suburban sections (800 acres) the Company had allocated to settlers or designated as Tenths as Occupation Reserves. Unfortunately, 800 acres of Tenths Reserves was relinquished to the Company to provide these Occupation Reserves and that area was not replaced.

47 acres of Nelson Town Tenths was taken without consultation with the Maori owners by the Governor in 1847.

In 1848-1849, another 300 acres of the Motueka Tenths was re-designated as Occupation Reserves, and in 1862 a further 400 acres was similarly re-designated. These re-designations further depleted the Tenths Reserves portfolio.

In 1853, following minimal consultation with Māori, Governor Grey granted land at Motueka to the Church of England to establish a school. Of the 1078 acres granted only 160 acres was Crown land. The remaining land comprised 429 acres of Tenths Reserves and 489 acres of Occupation Reserves at Motueka. Ngāti Tama people were among the families evicted from their Occupation Reserves which had been included in the grant when the school was established, and the Tenths estate was again reduced, by 429 acres.

Between 1847 and 1856 Crown agents purchased most of the remaining Māori land in Te Tauihu. These purchases in western Te Tauihu included land in which Ngāti Tama resided or held interests.

Government insistence on adherence to British-based laws and the English language was very destructive to both Te Reo and tikanga Maori, and the role of rangatira, which underpins tikanga, was constantly undermined by Government agents. Only whakapapa remained to hold the people together.

Hapu, whānau and individuals of Ngāti Tama were similarly affected, with many suffering ill-health, early mortality, poverty, destitution, marginalisation, despair and discrimination as a result of Government actions. A number of Ngāti Tama whānau ngā were forced to leave Te Tauihu in order to survive, and lost their connection with their turangawaewae.