Tūpuna of Ngāti Tama ki Te Tauihu

Various Tūpuna of Ngāti Tama ki Te Tauihu forged alliances, fought battles, led heke and taua to secure manawhenua and ahikāroa for Ngāti Tama ki Te Tauihu. Here are some of the stories.

Te Pūoho ki Te Rangi, paramount chief of Ngāti Tama, was the son of Whangataki II from northern Taranaki and Hinewairoro from Kāwhia. Te Pūoho’s father is a direct descendant of Tamaariki, co-captian of the Tokomaru waka.

Through his mother, Te Pūoho traces his whakapapa to another co-captain of the Tokomaru, Ngararuru, and also to important tūpuna of Tainui, Aotea and Kāhuitara waka.

Table: Tūpuna of Te Pūoho ki Te Rangi

Te Pūoho was born at Poutama in North Taranaki, as an adult chief his main pā was Pukearuhe near Parininihi. He headed a large whānau, many of whom played significant roles in Māori and colonial affairs in Taranaki, on the Kāpiti Coast, in Wellington-Hutt and especially the Hutt Valley.

1818: Te Pūoho’s first known taua

Around 1818 Te Pūoho prepared a taua; a war party, consisting of Ngāti Toa from Kāwhia and Ngāpuhi from Northland to avenge the death of Te Pūoho’s female relative Te Kiri-Kakara; Ngāti Toa and Ngāpuhi. Te Pūoho with various support from Ngāti Toa and Te Āti Awa attacked Taranaki Tūturu Pā, including Tāpui-nīkau Pā, Tataramaika, Ngāti Rāhiri Pā and Te Taniwha before the taua returned home.

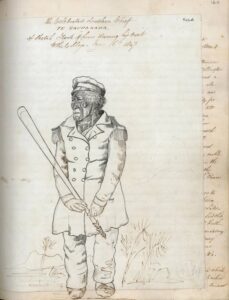

Image: This sketch of Te Rauparaha in 1847 is by William Bambridge

1820: Te Pūoho’s rising statusThen around 1820 another war party was brought together, led by Te Rauparaha of Ngāti Toa from Kāwhia and Tūwhare of Te Roroa from Northland. The formation of the taua, for Te Pūoho, was to seek utu for the kanga or curse he believed was placed on his daughter, by her husband, a son of Whanganui chief, Takarangi. A thousand fighting men fought their way as far south as Te Whanganui a Tara (Wellington Harbour).

While at Ōmere, overlooking Cook Strait, the sight of passing sailing ships prompted the Ngāpuhi chiefs to encourage Te Rauparaha and his people to migrate south to establish trading arrangements for arms and other goods. On the taua’s return journey home they continued to attack various Pā at Whanganui and many miles up the Whanganui River.

Te Pūoho’s status, rising from his high birth, coupled with his courage and fighting skills, qualified him for the position of paramount chief after his more senior relatives. As well as a fearless fighting chief, Te Pūoho was recognised as a high priest and acted as such to Te Rauparaha. Te Pūoho’s prowess and standing were also respected by his erstwhile adversaries.

1822: Te Heke Tātarāmoa, the Brumble-Bush Migration

Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Koata were ousted from Kāwhia districts by Waikato and Maniapoto and Te Pūoho escorted them from Mōkau to Kāweka, a few miles north of Urenui. Te Pūoho then decided to join other Taranaki hapū and their Kāwhia guests on a southern migration. He joined with Te Āti Awa from several hapū in a heke of around 2,000 people of all ages made the migration to Te Ūpoko o Te Ika (the Southern North Island). Te Heke Tātarāmoa encountered resistance from Ngā Rauru in southern Taranaki, but eventually reached the Kāpiti coast where Te Rauparaha settled temporarily at Waikawa near the Ōhau River.

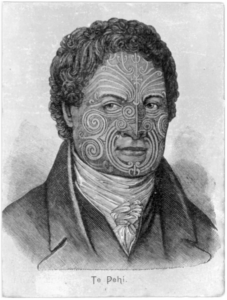

Te Peehi Kupe, Ngāti Toa’s paramount chief Alexander Turnbull Library,

During their short stay, other iwi conspired and raided the heke. Whanganui, Rangitāne and Muaūpoko iwi invited Te Rauparaha and his party to Te Whi Pā at Lake Papaitonga, there a number of Te Rauparaha’s own children, were killed as they slept. Te Ati Āwa returned to Taranaki, which forced Te Rauparaha to retreat to and fortify Kāpiti Island.

Te Peehi Kupe, Ngāti Toa’s paramount chief (and nephew of Te Pūoho’s wife, Kauhoe, and pictured left) lost his wife, Pohe, and four children in a raid by a Ngāti Apa party, he then travelled to England and Australia to acquire weapons for his future revenge. In the meantime, Te Pūoho returned to Taranaki to defend against further attacks from Northern tribes.

1823 – Te Heke Niho Puta (The Boar’s tusk)

Te Pūoho retraced his steps to Kāpiti with a large contingent of Ngāti Tama, accompanied by many Te Āti Awa led by Reretāwhangawhanga, Te Arahu, Te Poki and Ngātata, but some Tama remained at Poutama to maintain ahikāroa. 400-500 armed men, besides women (some also armed), children and old people, some were killed on the journey by Ngā Rauru.

There are varying witness accounts of the make-up and arrival of the heke to Kāpiti, one version of the migration is defined into four distinct heke:

- Ngāti Mutunga

- Ngāti Tama led by Te Pūoho and Te Rangitakaroro

- Ngāti Awa led by Reretāwhangawhanga, Te Manutoheroa, Te Tupe-o-Tū and Tākaratai

- Ngāti Raukawa led by Te Whatanui and Te Ahukaramu

North end of Kāpiti Island showing the site of a whaling station and the site of the 1823 battle of Waiorua.

In the meantime, Te Rauparaha had become safely entrenched at Kāpiti Island, exploiting commercial opportunities with whalers and traders. He built up an arsenal of weaponry and established relationships with ship captains and traders to enhance his position in inter-tribal affairs.

1828 – Following Whakapaetai

Te Ruaoneone of Rangitāne at Wairau and Te Rerewaka of Ngāti Kurī hapū of Ngāi Tahu at Kaikōura issued insulting threats at Te Rauparaha and his allies who harassed Kurahaupō people at Kāpiti, Horowhenua and Manawatū districts. Te Rauparaha responded with raids. It is probable that Te Pūoho and Ngāti Tama joined Te Rauparaha on the raid on the Wairau districts. After laying waste to many of the pā and kāinga throughout the Marlborough Sounds, Wairau and Pelorus districts, the combined taua regrouped and were joined by Te Peehi Kupe, paramount chief of Ngāti Toa who had returned from England and Australia with an arsenal of weapons.

After a preliminary raid that captured Wakapuaka, the alliance divided into two brigades. Te Rauparaha and Te Peehi Kupe led a contingent of mainly Ngāti Toa to attack east coast districts. The other taua, of Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Tama, set out to attack districts to the west; Te Manutoheroa and Te Pūoho took the lead in this invasion. Te Pūoho and some of his party, finding no one at Wakatū proceeded overland via Waimea while other Tama warriors coasted towards Motueka in their waka, at Waimea Te Pūoho planted his rākau in the whenua to signify his mana over the area.

Continuing westward, Te Pūoho’s party found Te Manutoheroa’s Te Āti Awa party at Ngāti Apa’s Te Mamaku Pā, which had been abandoned. While some of the Tama party may have been involved in the assaults on the Motueka and Riuwaka districts, Te Pūoho and most of Ngāti Tama proceeded to Pukatea (Astrolabe on the Abel Tasman coast).

Te Pūoho resided in Mohua for a period before returning to the North Island. Some Ngāti Tama, including members of Te Pūoho’s families, remained in Te Tauihu to maintain manawhenua over Tama’s interests in the conquered lands at Te Tai Poutini, Te Tai Tapu, Mohua, Motueka and Wakapuaka.

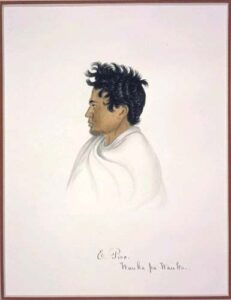

A portrait of Paremata Te Wahapiro painted in the early 1840s

1831 Te Heke Tama-te-Uaua and destruction of Kaiapoi Pā

While at Poutama in Taranaki, Te Pūoho decided on another Tama migration, Te Heke Tama-te-Uaua. The heke departed Taranaki, arriving at Kāpiti in late 1831, in time to join Te Rauparaha’s expedition to Kaiapoi which brought about the destruction of Ngāi Tahu’s major Pā there.

Te Pūoho and his son/nephew, Paremata Te Wahapiro realised that Taiaroa from Ōtākou, whom they had met and befriended at Kāpiti some years previously, was trapped within the beleaguered pā. They managed to get Taiaroa and his party safely out of the pā before it fell, an act of clemency Taiaroa was to repay to Paremata at Tūtūrau, 5 years later.

1833 – Te Heke Hauhaua

Te Pūoho returned to Taranaki to organise another migration of Ngāti Tama. He migrated his heke to the Kāpiti coast where there seemed to be unrest because of competition for land and other resources. The situation was exacerbated by the arrival of each new heke from Taranaki or Maungatautari. Scarcity of good land on the Manawatū/Horowhenua/Kāpiti coast influenced Te Pūoho’s decision to continue south to Te Tauihu.

Ngāti Tama left Kāpiti in thirteen canoes, three of which belonged to Te Pūoho; Tāhuahua, Te Wera and Te Kōpūtara. Once in Te Tauihu Te Pūoho did not remain there for long, it appears that as rangatira his role was to ensure the Tama migrants were safely settled on the lands at Wakapuaka, Motueka, Mohua and Te Tai Tapu. He did live at Parapara in Mohua for a period, and from there maintained Tama’s other holdings in Mohua and Te Tai Tapu.

1835 – Te Pūoho plans to attack Ngāi Tahu

By 1835 Te Pūoho was back on the Kāpiti coast, where it was said he was becoming a pawn under that of Te Rauparaha’s devious plots. Te Rauparaha’s desire to seek revenge on Muaūpoko, Rangitāne and other Kurahaupō iwi for the killing of his children lead him to devise an elegant series of exchanges, all according to tikanga which led to a feast hosted by Te Pūoho. Te Pūoho invited Muaūpoko, Rangitāne and Kurahaupō iwi to attend a large feast at Ōhariu. Soon after their arrival, Kurahaupō guests were set upon by Ngāti Toa and almost 400 people were killed. Te Pūoho was disgusted by the attack and able to save few Muaūpoko.

Te Pūoho left the North Island in February 1835 and on his travel to the South Island he crossed paths with Te Rauparaha who was on his way back to Kāpiti after being bested by Ngāi Tahu at Kapara-te-Hau (Lake Grassmere). Te Pūoho declared that he was intending to conquer and imprison Ngāi Tahu throughout the South Island.

Te Pūoho returned to his pā Rotokura/Cable Bay at Wakapuaka where he began organising the taua to attack Ngāi Tahu. From there he proceeded westwards via Moutere, Motueka, Abel Tasman coast, Mohua and Te Tai Tapu, recruiting fellow chiefs and warriors, and ensuring that Tama pā and kāinga would be appropriately garrisoned and overseen during his absence.

A number of Te Pūoho’s whānau remained in Te Tauihu, including his sons, Hori Te Karamu, Herewini Te Roha and Wī Katene Te Pūoho. His stepson/son, Paremata Te Wahapiro joined the taua, including Te Āti Awa, in accordance with tikanga.

December 1836 – January 1837

Te Pūoho’s epic journey down the west coast of the South Island and through the Southern Alps to where he met his eventual fate at Tūtūrau in Southland. The turbulent life of Ngāti Tama’s last customary chief was ended by a gunshot and the lives of many members of his party were lost. Paremata Te Wahapiro was spared through the intervention of Taiaroa, in repayment of the debt incurred at Kaiapoi. Kauhoe, Te Pūoho’s widow composed a famous lament for her husband and son, Paremata, whom she believed to be dead as well.

Summarized from: Ngāti Tama ki Te Waipounamu Trust, 2020; H & J Mitchell (2014), Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka, A history of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough

TO BE CONTINUED

TO BE CONTINUED